Clowns Without

Borders Guatemala

Journal, January 2006 February

4, 2006 Report

by David Lichtenstein Clowns Without Borders USA is fresh

back from a trip to Guatemala.

This trip was launched with the idea of bringing smiles to children and

adults in the communities most affected by torrential rains and mudslides

caused by Hurricane Stan in October 2005.

Clowns Without Borders is an International organization that brings

laughter and relief to people affected by war and disaster all over the globe.

Clowns Without Borders website Over 1,000

people were killed in Guatemala, mostly by tremendous mudslides that drowned

houses and whole villages.

Rebuilding and replanting are still very much in progress in these poor

indigenous villages and many people are still on emergency food aid and in

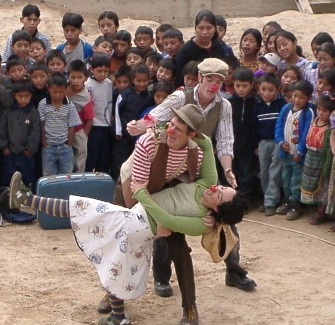

temporary housing. We performed

in Guatemala everyday from January 6 through January 18, 18 shows in 13 days,

entertaining over 6,000 people in extremely poor communities. We had a schedule targeting the

communities most affected by the hurricane, many of which are very difficult to

reach. Three clowns

make up the team, David Lichtenstein, an experienced CWB performer from

Portland, Oregon, and two performers new to CWB, Sayda Trujillo and Shea

Freedom Howler. Sayda is a

Guatemalan-American; we used her Grandmother«s house in the country, where

Sayda went to grade school, as a place to

rehearse our show for two days.

Shea had never been out of the USA before. Our first

show was in the TÃjutjil speaking aldea of Panabaj, in Santiago de Atitlan.

There, on October 5, 2005 at 4:00 in the morning, a giant mudslide originating

thousands of feet higher on the Volcano Atitlan buried much of the village,

killing 80 people, most of whom are still buried under the mudflow. The mudslide

snakes down 10,000 foot tall Volcano Atitlan Hospitalito AtitlÂn after the mudslide Crowded

temporary housing has been set up on top of the mudflow. We performed

on top of the mudflow that had buried 80 people, at the top edge of the refugee

housing. There were over 300 children, plus many parents. The show was

made difficult by strong gusting winds that swirled the volcanic ash of the

flow all over us, up our noses and throats and in our eyes. The children were rather rather

wild. Although they loved the

show, many threw rocks at us throughout the show. Others

grabbed at our props and we had to stop the show to move the crowd farther

back. One woman told us that

it was the first time she had seen the children laughing like that for months.

It was an extraordinary experience. We were also

able to visit (and bring supplies for) a farm run cooperatively by 70 families

of the village. Several villagers

are graduates of the animal husbandry school run by CAPAZ. Their entire animal raising operation

and coffee processing area were buried in 5 feet of volcanic mud, killing all

animals and losing much of their crops.

They have already heroically dug all the most essential parts of the

farm out from under more than mudflow by hand, and Pieter has found donations

to replace some of their animals.

Unfortunately it is not possible to grow anything in the volcanic sand

and ash of the flow. Dying crops

buried in 5 feet of volcanic mudflow This coffee

drying area has been dug out from 5 feet of mud. January 8th

and 9th Clowns Without Borders visited two isolated and very poor coffee

fincas. Lots of hours bouncing around in the back of a jeep. January 8th

we went to Finca La Candelaria above the pueblo of Pochuta. We were down in the hot lowlands at the

beginning at the hills. About 250 people packed around a concrete slab. They laughed like hyenas and we played

for almost two hours, which made us quite proud since we put this show together

in a few days after not even knowing each other beforehand. The people were as friendly as could be

and some of the child volunteers were true clowns. January 9th

we repeated this experience at La Florida Finca near the town of La Columba in

a fold of incredibly steep hills covered with coffee plantations and scrub

jungle. About 200 people laughing

themselves silly at this show. Both of

these fincas are large coffee plantations that originally belonged to single

owners. When the owners abandoned

them as unprofitable the workers, about 100 dirt-poor indigenous families at

each one, claimed and squatted the land. After some

years of negotiation with banks they now own the land and work it

cooperatively. But they have to

pay the banks off. At La

Candeleria all the money from each years coffee crop is dedicated to paying off

the land, which they think they can do in 7 years. Thus, besides working their own land all the families need

to go work at nearby plantations to earn money to live on. Unfortunately, they lost much of this

year«s crop to the hurricane«s mud flood. (I died

every show. Death of a Clown.) At La

Florida, the crowd was smaller because, the day of the show, most of the men

trucked off to a town to support other poor workers, who apparently were

threatened with getting their homes repossessed because of debt. Their coffee hillsides are badly grown

over and decimated. For their first year of squatting they had almost no housing

at all and still they are very crowded.

In the old house that belonged to the original German owners, 12

families are packed in. They have

a lumber saw and a corn grinder powered by a water mill. The steep

hills we drive through are sprinkled with hundreds of landslide scratches of

exposed dirt, many of them thousands of feet long. There are many washouts in the road, most of them reasonably

repaired three months after the hurricane. We have been trying to do a show in the

Central Park of our host city of Quetzaltenango. On January 6th we had started a show on the central square

but the police came to stop us.

The crowd booed and heckled the police but we calmed them down and

moved, as instructed by the police, to a filthy stage near the market. We had a

wonderful show there for about 250 people, mostly poor market children plus

some families and a sprinkling of tourists. We knew we

could get a huge crowd in the Central Park so on January 10th we petitioned

City Hall, got a letter typed up explaining Clowns Without Borders, signed by

three officials and still were refused in the end. The Chief of Police felt that we had been upsetting his

authority in our first show in some way and swore at us rudely. The mayor, the only person who could

overrule him, never showed up. So

instead we went to Park Benito Juarez to play. We had a fantastic show there for about 500 people including

perhaps 100 homeless street children and shoeshine boys. (Pieter

caught a street boy sniffing glue in the audience of our show at the Xela

Mercado) On January

11, with the support of the San Juan Ostancalco office of woman, children and

human rights, we performed for two schools in a very poor hillside barrio of

that town. At the first school,

Communtaria Los Lopez, we had 450 kids and 50 adults absolutely in

stitches. At the Escuela

Communitaria Los Romero, we had to walk in a few hundred meters because of a

bridge that been washed out by the hurricane. There we played for about 300 children and 20 adults with

great success. On the walk

back to the truck I talked to a man living nearby. He had spent two years working in Michigan (although he

didn«t speak any English) and had earned money to construct a two story

concrete house and buy a pickup truck in his hometown. In many towns like this all over

Guatemala all the newer multi-room concrete houses are built with money from

immigrant labor in the United States. Current debate in the U.S. congress about

the new immigration law and the attempts of Mexico and Central America to

influence it are headline news here.

Most rural Guatamalans live in one room concrete blocks or shacks. On January

12, Shea headed back to the United

States to get ready for school, and Sayda and I headed for three distant

communities surrounded by the 4,000-meter volcanoes of Tajamulco and Tacana. Tajamulco

Volcano, over 14,000 feet tall I had been

struck by stomach sickness the night before and the trip was not easy. After a few hours of twisting, but

reasonable mountain roads we passed the Tajamulco Volcano and turned off on to

a smaller road. It was not a bad road, it was a

miraculous road. It was a miracle

that somehow the road kept finding a narrow path to twist down this knife edged

ridge and worm its way through landslide after landslide. Once we had to stop for a grader that

was making a way for the road through a landslide. When we

asked how long the wait would be they said Ãun ratitoÃ, -just a moment- and we

laughed. Spectacular

views. We were well past where the

ubiquitous buses and soft drink trucks could reach and yet still the road was

lined with villages, sometimes with one room concrete houses posed on

promontories between the road and precipitous drops. Marco and the Toyota Land Cruiser provide by Manos

Campesinas perform like heroes. Shortly before the previous end of the

road, a landslide has taken out three whole switchbacks of the road and we had

to get out and walk. Crossing

another landslide. It was about

and one and half hour hike steeply downhill to our first destination of

Carrizal. It was some of the

biggest, steepest mountains and canyons I have ever hiked in. My previous experience told me this

should be wilderness and yet we were hiking through a steep patchwork of coffee

and corn patches, many wiped out by landslides. La Unidad,

tomorrow morningÃs show is down below on the river. On the way

down, we ran into one of our guideÃs sons coming up with a mule, both mule and

boy well laden with crops.

Everyday the boy leaves the village at 3:00 to do a 7-hour portage trip,

crops go up, and store-bought goods come down. Today he was doing a double, which is why he was still going

up at noon. He was 16 years old

but looked 12. In the

village we were given a rich soup of chicken and jungle vegetables. I was exhausted and hadnÃt eaten since

yesterday because of my stomach sickness.

I took my chances and ate it and it went down well. No energy, but we start, and have a

wonderful show. The audience is

very shy, walk towards the audience to get a volunteer and the entire part of

the crowd stands up and runs away.

Somehow, like in every other show, I found a perfect child volunteer for

the first long volunteer play. By

the end there were 350 laughing villagers. After the

show we hiked further down to the bottom of the canyon. La Unidad is located where two rushing

mountain streams join together to form the Suchiate River, which lower down

forms the border between Guatemala and Mexico. The riverbed is filled with giant boulders, many larger then

houses. There used to be high

suspension foot bridges over each stream but the hurricane rains washed one

away; several houses were, too. House sized

boulders on the Suchiate river and the foundations for the destroyed bridge on

the lower left. We are again

fed delicious chicken soup and nearly clear coffee served in used soda bottles

that we avoided as a bad water risk.

We eat by the light of a single candle, hours of walk away from the

nearest electricity. We spend the

night in the church back room, sleeping on pews. On the blackboard is a list of food aid and thanks to the

agencies that provide it. We go to

sleep at 7:00 in the evening and wake up at 6:00 in the morning. We have

another wonderful show, although the villagers are so shy that we spend many

minutes of the show begging for volunteers. The crowd builds slowly up to 300 as the people trickle in

from various parts of the canyon.

Then itÃs time for the hike out.

As usual, the villagers carrying our bags race ahead while we plod up

the vertical path. This man is

carrying my baggage for me. Below

at his right elbow is the village of La Unidad where we did this morningÃs

show. Three hours

of hiking and three hours of driving back to the main road, over a 3000 meter

pass and more bad road to the end of the main road and the village of

Tacana. There an

outlying community called Cua had been hit by a mudslide that killed 47

people. Close to the mudslide, the

community is holding a town meeting. The

landslide and village of Cua We had been

unable to contact this community so we pull a few town leaders aside to explain

Payasos Sin Fronteras and propose a show for the next morning. They quickly agree and even offer us

hotel lodging in Tacana. The hotel is

fine except that there is no water or electricity in our room. The next morning we have another

excellent show for about 400 laughing townspeople. Right next to our show workers are busy building a new

community center and we have fun improvising with the workers. After the show we find out that just before the show, two childrenÃs

bodies had been pulled out of the mudflow and reburied. As we are

leaving they hook up the loudspeaker, point it up the hill and start asking the

community to bring buckets and pitchers of water. They are out of water and the workers canÃt pour any more

concrete until community members bring water. Indigenous villages seem to be naturally communitarian. These people are Mam speakers. There are 22 different Indian languages

spoken in Guatemala. Cua Walking back

to town we meet an American Peace Corp worker. He is the lone gringo in this townand he is trying to teach

local communities about forestry and replanting, which is badly needed. The centuries-old pattern of Indigenous

people being pushed higher and higher into the mountains to find subsistence

corn plots, called milpa, is still going on. The people cut down the trees for firewood and the milpa,

aggravating the landslide problem when the rains hit. Guatemala is headed the direction of Haiti where the entire

island was deforested decades ago, changing climate patterns. The bus we

get onto to head back becomes the most crowded chicken bus in the world. I have a large woman with a turkey in

her arms sitting mostly on top of me and unbelievably the driver keeps stopping

to take on more people. At

its most stuffed, the bus breaks down, and people mock the driver. After a while they fix it, 15 men get

out to push start the bus and we move on.

The second bus we get on breaks down, and this time they donÃt fix it,

leaving us on the side of the road, hitchhiking in competition with 60 other

passengers as night falls. We pile

into the back of pickup truck with several others and receive a freezing ride

over a mountain pass to the comforts of PieterÃs house in Xela. Hitchhiking

from the broken down bus as night falls. January 15

-18 we did several school and community shows in the poor towns of San Juan

Ostuncalco, Concepcion, and two poor distant barrios of Quetzaltenango. January 17

is particularly enjoyable in that we do three schools in Concepcion in a very

well organized tour put together by Victorina Lopez, who works for the city of

Concepcion. The first school is

newly constructed and requires a short walk-in because of a washed out

bridge. The next two schools

provide us with large happy crowds.

We are

accompanied by a Harvard researcher whose name I have forgotten. He and others have been studying the

health effects of indoor air pollution.

They have found that indoor wood fire smoke doubles the incidence of

respiratory diseases and pneumonia is the number one killer of children in

Guatemala. They are studying to

see how much the rate of respiratory and cardiac disease can be reduced my

providing more efficient wood stoves that smoke much less. Victorina

says the current population of Concepcion is 15,000 and there are 6,000 people

from Concepcion in the United States.

This town is an extreme, but nationwide, the money remitted from

Guatemalan workers in the United States is bigger then that brought in my

GuatemalaÃs biggest exports (coffee, sugar, and bananas) and easily dwarfs all

foreign aid. David,

Victorina Lopez, Sayda, and the principal of Escuela Telena-Tzicol On the last

day, January 18 we visit Pacaja Alto School in one of the poorest barrios of

Xela, tucked under the Santa Maria volcano. We are brought there by CEIPA, an organization that serves

worker children, young children who work as market sellers, shoeshine boys,

etc. They find ways for the

children to attend some kind of school or training while keeping the jobs they

need to survive. Many have been

placed in the Pacaja Alto School. We have our

18th and last successful show on a grassy mound in the sun and wind

at 7,600 feet of altitude, below the Santa Maria volcano. We had made more than 6,000 people in

many distant communities laugh. No

child without a smile! Escuela Pacaja Alto and the Ãschool yardà in front List of Shows: January 6 Panabaj,

Santiago de Atitlan 350 people January 7 Quezaltenango

Mercado 250 January 8 Finca

La Candelaria, cerca de La Pochuta 250 January 9 Finca

La Florida, cerca de La Columba 200 January 10 Parque

Benito Juarez , Quetzaltenango 500 January 11 Barrio

La Victoria, San Juan Ostuncalco Escuela

Los Lopez 500 Escuela

Los Romero 320 January 12 Carrizal,

Tajamulco, San Marco 350 January 13 La

Unidad, Tajamulco, San Marco 300 January 14 Cua,

Tacana, San Marcos 400 January 15 Llanos

del Pinal, Quetzaltenango

200 January 16 San

Juan Ostuncalco Escuela

La Union Los Mendoza 400 Escuela

Agua Tibia 350 Escuela

Los Escobares 200 Jan 17 Concepcion,

Chiquirichapa Escuela

Caseria Tojcoral 145 Escuela

Telena - Tzicol 550 Escuela

Barrio San Marcos 400 Jan 18 Pacaja

Alto, Quetzaltenango

475 18 Show in 13 days and over 6000 laughing people! Friends and aiding organizations Our

principle local organizer was Pieter Van Nestelrooy who runs CAPAZ, an

organization that teaches commercial animal husbandry and supports establishment

of cooperative farms in indigenous communities, including the cooperative farm

at Panabaj. Pieter organized the

tour by contacting all the organizations and communities and generously put up

the Payasos in his Quetzaltenango apartment. Pieter in

his native habitat We are also

supported by Manos Campesinos, who organize small coffee farmers to get fairer

prices for their coffee. Evelyn

Rodas organized 5 of our shows and Marco did the tough driving out to Tajamulco

and Tacana. Find out

more about them at

Louie's CWB center

Clowns Without Borders website

http://www.manoscampesinas.org

Kevin Romero

of the Alcalde of San Juan Ostuncalco brought us to 5 schools in poor upper

Caserias of that town.

Victorina

Lopez of the Alcalde of Concepcion brought us to three wonderful schools.

Proyecto Payasos is a Gautemalan organization that does AIDS education through the medium of clown shows and workshops. GuatamalaÃs poverty, poor education, and language/ethnic isolation puts it as risk of an potential explosion in AIDS/HIV infection. Proyecto Payasos does amazing work the fun way. This large collective has done itÃs work in 12 of GuatemalaÃs 22 indigenous languages. Thanks to Stephan.

http://www.proyectopayaso.org

Rolando Morales, Margarita Tay, and Esther Lux do wonderful work

with CEIPA and organized our final show.

Our friends, Elena and Marjolaine, befriended us, drank with us, and drove us to the first show at Panabaj. They work with Chilam-Balam, an organization that works with Mayan artisans to create a unified catalogue of artistic textile products to sell in Europe and the USA with the idea of maintaining fair living wages for the artists, loom artisans, and dyers.

http://www.chilam-balam.org

I met two volunteers who worked with an Guatemalan organization called Maya Pedal that builds and distributes low-tech bicycled powered machines for grinding corn, pumping water, fabricating ceramic roofing tiles and other purposes.

I met and juggled with an enthusiastic group of young jugglers in Guatemala City, including Seidy and Selvyn. Some of them work with a physical theater group in Guate called Caja Ludica .

I met Andy, volunteer director for Ak Tenamit , an organization that works with fighting poverty and educating youth on the beautiful jungle river, Rio Tatin, a tributary of the Rio Dulce. They lost their volunteer that teaches circus and stilts to the kids, an opportunity for one of you circus folks out there. However they are only interested in serious people-- which means work very well with youth, speak Spanish, minimum 6 month commitment.

I met a taxi driver who worked with an evangelical group that works with children of basureros at the Guatemalan city dump called the Potters House Association . Basureros are people that work in, and usually live next to, large city dumps; adults and children eke out a living by collecting recyclable materials. (A world wide phenomena)

I am fascinated by different ways that organizations try to help people stuck in poverty in developing countries and would like to try doing it full time myself someday.

Louie's CWB center

Clowns Without Borders website